Freedom of speech is the cornerstone for maintaining open societies where dialogue, dissent, and exchanging ideas are cherished. It gives people the right to hold opinions without interference and express these views in public.

Australia is known globally as a robust democratic nation. It presents an interesting case study of how freedom of speech is interpreted, practised and challenged. Unlike counterparts like the United States, which enshrines the right to free speech in its Constitution, Australia’s lack of a Bill of Rights makes the landscape for free expression more complex and often subject to legal and societal debates.

Does Australia have freedom of speech?

The Australian Constitution doesn’t have explicit text like the United States’s First Amendment, which protects freedom of speech. However, the High Court has acknowledged an implied freedom of political communication, not as an individual right, but as a necessary corollary of the system of representative and responsible government created by the Constitution. This freedom, however, is not absolute and has often clashed with laws aimed at maintaining public order, preventing defamation, and securing communications related to national security.

Article 19 of the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights states:

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

But this is not Australian law and is only an aspirational vision of the way things should be.

A balancing act: anti-discrimination, defamation, and national security

The balance between free speech and preventing harm to individuals and society is delicate, as there will never be complete agreement on a freedom of speech definition. Australia has stringent anti-defamation and anti-discrimination laws, protecting individuals against speech considered harmful or hateful. While these laws might protect the rights of individuals, they raise important questions about where the line is drawn between criticism and defamation or between offensive speech and hate speech that can insult, humiliate or intimidate people.

For example, heated political speeches attack the opponent’s or opposing party’s character. In October 2012, Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard accused Tony Abbott (the Coalition opposition leader) of being a misogynist. She offered no proof that Mr Abbott hated women. He had said a few things in the past, such as, “…but what if men are, by physiology or temperament, more adapted to exercise authority or to issue command?” But this doesn’t mean that he hates women. He should have the freedom to hold opinions that people don’t agree with.

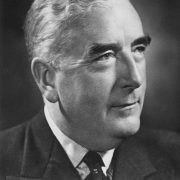

Another example is Robert Menzies. He used powerful language (which many people today would call offensive) as the leader of Australia’s Liberal Party when the Labor Chifley Government tried to nationalise Australia’s banks in 1947. Menzies spoke with great fervour against this move.

In an August 1947 speech, he called the Labor Party’s proposal a “superb instrument of tyranny.” He also compared the move to nationalise Australia’s banks to the actions of Germany’s fascist leaders, who had been defeated only two years earlier. While some might consider this offensive, Menzies was exercising his freedom of speech.

Although not an Australian example, US President Ronald Reagan was known for his strong language when confronting the Soviet Union during the Cold War. He was criticised for his bold language, such as during his speech to the National Association of Evangelicals (on March 8th, 1983), when he used the term “evil empire” to describe the Soviet Union.

Another example of Reagan’s use of strong language is found in his Address at the Brandenburg Gate in West Berlin (June 12th, 1987). Peter Robinson was a speechwriter in the Reagan White House and went to Berlin weeks before the president’s visit to research for the upcoming address. He visited the Berlin Wall and spoke to local residents. While the US diplomats told him not to mention the wall in the speech because the local people were used to it, the residents of Berlin told Mr Robinson they hated it. In response, the Berlin Wall was mentioned in the speech, including the famous line, “Tear down this wall!”

In the days preceding the delivery, White House staff members voiced their opposition to the line that could offend the Soviet leadership. But President Reagan insisted that it remain in the speech. This line has made it one of the most admired speeches of the 20th century. Now, with a historical perspective, it’s clear that Reagan’s strong rhetoric – which some considered insulting and humiliating – played a large part in ending the Cold War and freeing millions from communism.

In today’s world, the important and impactful speeches of leaders such as Menzies and Reagan would be considered offensive by some who would call for censorship.

Digital Age, media, and misinformation

With the advent of the digital age, freedom of speech has encountered new frontiers in Australia. Social media platforms have become modern-day public squares. However, they also bring challenges, such as the rapid spread of misinformation. The Australian government’s recent clashes with tech giants like Facebook and Google over news content and misinformation indicate that the nation is grappling with maintaining a free and open internet while preventing the harms of unregulated speech.

In media, the concentration of ownership has sparked debates on media pluralism and the diversity of viewpoints, which is essential for a healthy representative democracy. The recent raids on journalists and media houses by federal police, under the pretext of safeguarding national interests, have raised domestic and international concern over press freedom in Australia.

More recently, freedom of speech has come under attack in Australia. during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diverse views on alternative treatments, the dangers of accepted treatments and the failure of lockdown measures were censored by governments. Frighteningly, at one point, New Zealand’s Prime Minister told New Zealanders the government should be the sole source of “truth” about COVID-19. In retrospect, much of the information from governments worldwide – including Australia’s and New Zealand’s – turned out to be false and even harmful, resulting in deaths and terrible side effects. Much of what governments labelled “misinformation” was true, and open debate would have led to less damage to lives and livelihoods.

Inconsistent application of freedom of speech

There is much focus on how freedom of speech can be misused to offend, insult or humiliate members of minority groups, such as indigenous Australians. Terms used in the past to negatively describe members of these groups are now frowned upon. While this is positive, it raises the question of double standards regarding how people impart information and ideas.

For example, the term “pale, male and stale” is used to describe older men of European ancestry, especially in positions of power, such as on company boards. This offensive term is used in public speech and in print. But if you used such a term to describe members of another group – such as a minority group – there would be an outcry against it. This highlights the tendency for restrictions on freedom of speech to be lopsided against groups traditionally in the majority and held more power in Western countries.

Public sentiment and the way forward

The Australian public’s sentiment towards freedom of speech often reflects a desire for balance. While there’s substantial support for uncensored political discussions, there’s also a recognition of the potential harms of unbridled speech, leading to societal or individual harm. But in the long run, it’s in the public interest to maximise the benefits of free speech, if only feelings are hurt, there’s no incitement to violence, and physical harm is done.

The future of Australian freedom of speech

Freedom of speech in Australia is a dynamic and evolving discourse, reflecting the nation’s democratic values, societal attitudes, and historical context. The absence of a constitutional directive – such as a Freedom of Speech Amendment – results in a scenario where legislative and judiciary measures continually shape and redefine the boundaries and implications of free speech. The danger is that legislators and judges can be biased to favour free speech for certain groups over others. This bias is exacerbated by power groups – such as big tech, academia and mainstream media – which tend to hold similar beliefs.

As Australia moves forward, the global context, technological changes, and domestic societal shifts will further influence how Australians perceive, protect, and practice free speech. The ongoing challenge lies in balancing diverse viewpoints, safety, and security to ensure that Australia remains a society where free speech contributes to its democratic fabric and respects people’s rights.

As professional speechwriters, we’ll continue to support freedom of speech in Australia, regardless of any attempts to curtail it.

Image by Freepik